In an earlier post regarding CRS, Bill Caudill and his TIB's, I mentioned CRS's commitment to research, and that I'd be returning to his "Things I Believe" and their relationship to current architectural issues. Flipping through the book, I came across the following TIB on research from Bill in April 1966.

"There are a lot of definitions for research.

I like this one:

'Regarding the search for truth'

It even looks good:

RE:SEARCH"

A few weeks ago I came across some new information on CRS. In her excellent paper, Marketing through research: William

Caudill and Caudill, Rowlett, Scott (CRS), Avigail Sachs provides historical analysis of the "research attitude" of the firm in its formative stage. She notes their power to integrate professional practice and research, in both marketing and design, while leading the AIA and profession in applying research and new techniques to the design world. In her conclusions, she advises contemporary architectural practices to learn from CRS's early stage commitments to research, scholarship, marketing and design leadership. Though many contemporary A/E firms have benefitted by engaging research in their practice methods, the profession still has a long way to go to bridge the research/practice gap.

For example, a few months ago I prepared a short paper in our firm, advancing the argument that architectural programming is actually primary research. The word research often has multiple meanings and requires a variety of skills that many architects and engineers are not trained to perform. Most design professionals understand that primary research is the collection and evaluation of data leading to knowledge that does not already exist, but what isn't clear to practicing professionals, is the linkages between architectural practice and design research. Looking at our profession and our firm's design practices, one might raise the question, what parts of our current methods are or could be defined as research and how as a firm and profession can we better understand and refine these methods.

In his book, Inquiry by Design, John Zeisel sets out some basic concepts regarding the relationship and cooperation between research and design, from the perspective of an environmental behavioral researcher and a designer. He argues that designers and researchers can work together to solve more broadly defined design problems than they could each solve alone. A major issue, however, is the usefulness of research material. It must be in a form that designers can not only use, but in turn, improves the chance that research information can be tested in practice. Research investigators learn by making hypothetical predictions, testing ideas, evaluating outcomes and modifying hypotheses. These activities are the basis of their collaboration and cooperation.

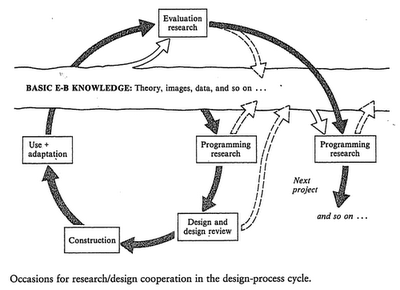

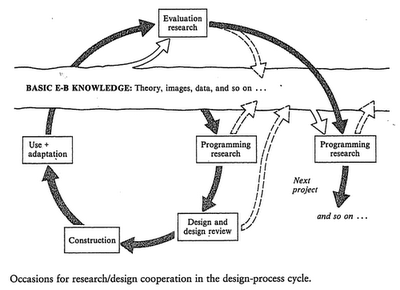

Zeisel states that there are at least three day to day design practices that offer opportunity for research/design cooperation.

1. Design Programming: research for the design of a particular project

2. Design Review: design assessment for conformance with exis

ting environmental behavioral research knowledge

3. Post Occupancy Evaluation: assessment of built projects in use in comparison with original design goals/hypotheses

This diagram is from Zeisel's text and describes the relationship between environmental behavior knowledge and the design process.

Of these three project practices, a revised approach to programming offers a major opportunity to recognize its research nature, improve our methodology, and create a basis for innovation and idea generation. In some ways over the past forty years, programming has moved from a very specialized consultant service into a more mainstream process, often blended with services like planning, master planning and concept design. Thus the discipline of programming has become blurred.

Perhaps a step back in recent history would be useful. Two important books were published forty years ago, Problem Seeking, by CRS and Emerging Techniques 2: Architectural Programming, published by the AIA. Both books presented the emerging practice and techniques which systematically defined quantative and qualitative facility needs. It was a predesign process and was viewed as specialty practice. In Problem Seeking, the classic quote and discipline separation was stated as "Programming is problem seeing, design is problem solving." As conceived and practiced, the programming research team was distinct from the design team and the program document was a thorough analysis and documentation of facility needs. It could stand alone as both a statement of requirements and as an evaluation tool for any design response to facility needs. A quote from the AIA Architects Guide to Facility Programming underscores the research perspective.

"It (the program) lays the foundation of information based on empirical evidence rather than assumption that helps the designer respond effectively and creatively to client requirements and facility parameters and constraints."

"Programming is an information-processing process. It involves a disciplined methodology of data collection, analysis, organization, communication and evaluation through which all human, physical and external influences on a facility's design may be explored."

The opportunity then is to reassess the methods, tools and techniques currently used to program within our profession, practices and building typologies. Considerable effort has been invested in developing templates and formats for quantative program/space needs and related programs. However a bigger opportunity still exists in regard to a wide variety of methods available to conduct primary research/facility program requirements. In Robert and Barbara Sommer's book, A Practical Guide to Behavioral Research, Tools and Techniques, they define the full array of methods appropriate for programming as research. Four basic techniques are defined: observation, experiment, questionnaire, and interview. When thought about specifically as programming, these techniques are most realistically practiced as a multi-method approach, combining observations, interviews and questionnaires, as well as case studies. The following outlines the techniques as both definition and reminder:

- Observation: includes casual observation, systematic observation, video recording, photographic recording, and behavioral mapping and trace measures.

- Interview: includes unstructured interviews, structured interviews, semi structured interviews, telephone interviews and focus groups.

- Questionnaire: includes open end and closed questions, ranking versus rating questions, matrix questions, group or individual survey, mail survey and internet survey.

I believe we should take Avigail Sach's advice to heart. We should learn from the early CRS "research attitude", look to the roots of architectural programming as a discipline, and as John Zeisel does, define programming as primary research.